Barron’s, the financial investor publication, conducted an overall “credit worthiness” scorecard for states and ranked Connecticut near the bottom of the pack, despite a hefty budget reserve fund.

Connecticut currently has an A1 stable credit outlook from Moody’s Investor Services and an A rating from S&P Global Ratings.

However, according to Barron’s assessment, Connecticut’s high debt burden put Connecticut near the bottom of the list.

The list was compiled and analyzed by Eaton Vance who wrote that Connecticut was “the state with the highest overall debt burden on a per capita basis and a per GDP basis.”

Connecticut’s debt and unfunded liabilities related to state employee and teacher retirement benefits amounts to 33 percent of the state’s gross domestic product, according to Barron’s.

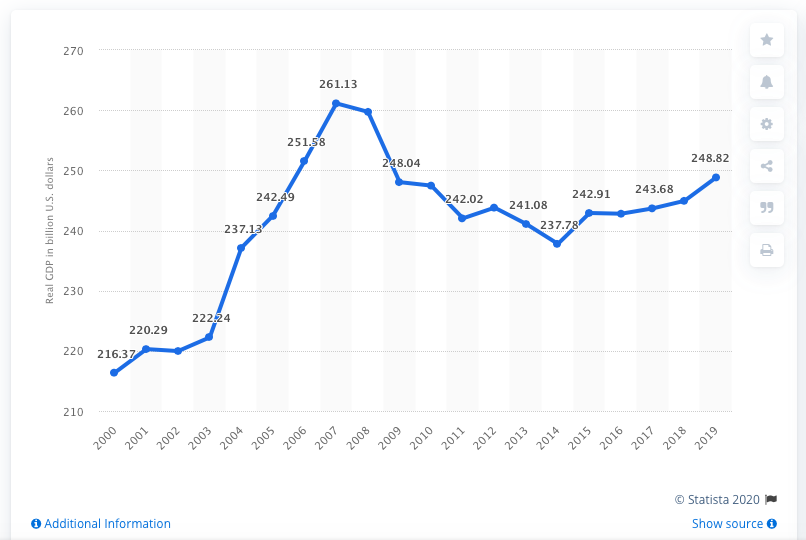

According to Statista, Connecticut’s gross domestic product in 2019 was $248.82 billion, well below the state’s peak performance in 2007 when GDP was $261.13 billion.

Meanwhile, the national GDP rose from $14.4 trillion in 2007 to $21.4 trillion in 2019.

Connecticut’s GDP bottomed out in 2014 and the state’s economy has only grown 4.5 percent since that time, according to Statista.

Connecticut’s long-term debt was listed as $32.4 billion in 2014, but that figure did not include pension and retiree health benefit debt, which added an additional $47.8 billion in unfunded liabilities for a total of $80.2 billion, according to the state’s 2014 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report.

By 2019, the state’s long-term debt was listed as $83.1 billion or 33 percent of Connecticut’s GDP. The debt includes $26.7 in bonded debt for governmental activities and $54.72 billion in unfunded pension and retirement liabilities.

That amounts to roughly $2,331 per person in the state.

In Truth in Accounting’s 2019 report, it was estimated that Connecticut’s debt burden amounted to $51,800 per taxpayer, based on Connecticut’s debt in 2018.

Debt, both bonded debt and those related to pensions and retiree healthcare, are part of Connecticut’s fixed costs, which, along with Medicaid payments, grow at roughly $550 million per year, according to the Office of Fiscal Analysis.

Fixed costs comprise half of Connecticut’s budget and are expected to grow from $10 billion this year to $11.5 billion by fiscal year 2024.

In their latest budget analysis, the OFA projects Connecticut will face deficits in the next three years ranging from a little more than $1 billion to just under $1.4 billion, largely due to the economic downturn and COVID-19 pandemic.

Better than expected revenues from fiscal year 2020, pushed Connecticut’s rainy day fund to its $3 billion maximum, but it is difficult to say how future revenues will be affected with the ongoing economic slowdown.

Connecticut’s bond rating has been stable for a couple years following downgrades between 2016 and 2018 due to Connecticut’s eroding revenue and unfunded liabilities.