Connecticut entered the COVID-19 pandemic with roughly half the money in its unemployment trust fund needed to withstand a typical recession and subsequently, the state had to borrow $894 million from the federal government in order to pay unemployment claims that surged in 2020.

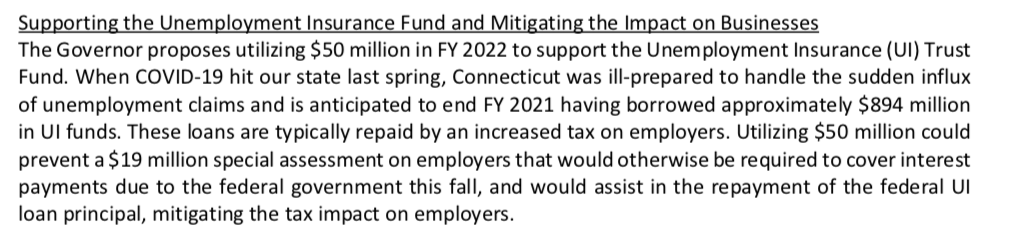

Now, with the federal government sending the state a $2.6 billion slush fund to be used for fiscal recovery, Gov. Ned Lamont has proposed paying back $50 million of the borrowed unemployment money, leaving Connecticut businesses on the hook for the remaining $844 million.

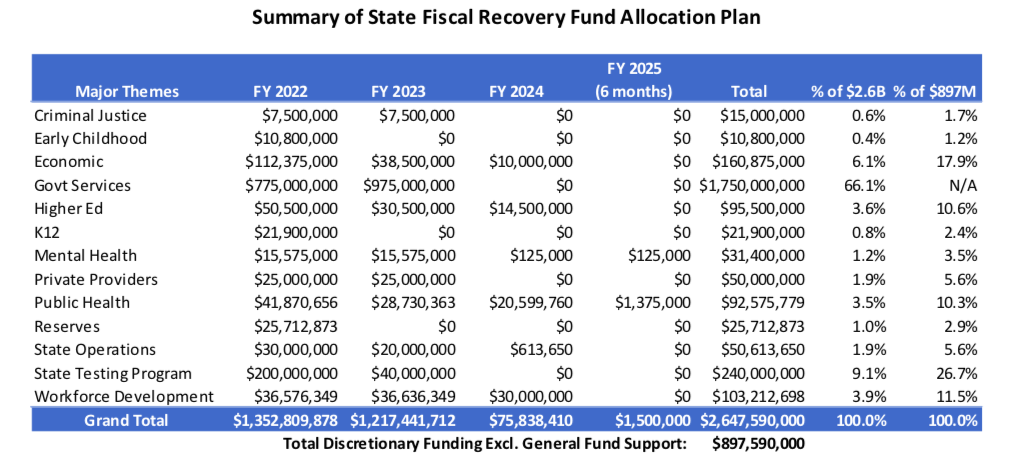

The vast majority of the federal government’s fiscal support funds — $1.75 billion — will be used to bridge projected budget deficits, and the remaining $897 million will be split between other economic mitigation proposals, public health, social and education programs, according to the governor’s proposal.

Connecticut businesses were forced to pay back $1.2 billion in unemployment borrowing from the federal government for the 2008 recession, which resulted in a typical employer’s federal unemployment insurance payment jumping from $42 to $192 per employee between 2010 and 2015, according to the Connecticut Office of Legislative Research.

Lamont’s presentation on how he hopes to allocate federal relief funding says the $50 million payment will relieve Connecticut businesses of $19 million in interest payments.

Eric Gjede of the Connecticut Business and Industry Association says they’re grateful for the $50 million but were “hoping for a bigger commitment.”

Gjede notes that Connecticut businesses received no help from the state government for unemployment borrowing for the 2008 recession, so the effects of repaying this debt will not be as bad. “But, obviously, it’s leaving the vast majority of the burden on businesses for an economic downturn they didn’t create,” Gjede said.

The increased employee costs for businesses could affect Connecticut’s job recovery.

Connecticut’s current unemployment rate is 8.3 percent, a little more than two points higher than the national unemployment rate and the number of jobs is 7.2 percent lower than Connecticut’s pre-pandemic high, according the Connecticut Department of Labor’s Economic Digest.

The DOL’s latest short-term projections say Connecticut’s employment gains will outpace Massachusetts and recover all jobs lost during the pandemic by the second quarter of 2022. However, other economists have remained skeptical about Connecticut’s economic growth over the next decade.

The governor has also been working to prevent businesses from being assessed a higher unemployment experience rating due to forced lay-offs during the pandemic.

A bi-partisan agreement between the governor and legislative leaders from both sides of the aisle – along with the support of CBIA and the state’s labor unions – offered reforms to the unemployment system and partial relief for businesses affected by the pandemic.

When businesses lay off employees it affects their experience rating for making unemployment insurance payments, essentially making them pay a higher rate, similar to putting a claim in on car insurance which then forces the vehicle owner to pay more for insurance.

According to the governor’s press release, employers forced to lay off staff due to “sector-wide economic shocks” will face reduced experience ratings.

The agreement also adjusted Connecticut’s unemployment system going forward, increasing the taxable wage base, increasing the minimum amount of wages required to be eligible for unemployment and defers unemployment wages until after an employee has received their severance package.

While the unemployment reforms enjoy bipartisan support for passage in the General Assembly, Lamont’s proposals for how to allocate federal relief funds are also subject to adjustment and approval by the House and Senate under legislation passed earlier this year.

Connecticut’s surging tax revenues may allow lawmakers to allocate less federal funding toward the projected budget gap. The latest revenue estimates show Connecticut will have an additional $900 million to help make up the $1.6 billion two-year deficit.

But with legislators and advocacy groups clamoring for more funding of social services combined with the sheer size of the unemployment debt means businesses will likely be paying this debt for years to come.